As a source for student entertainment, college radio is growing increasingly obsolete. In the age of digital music streaming, most college students are far more likely to open Spotify or YouTube than to tune into a local FM station—after all, few students even own a radio. It’s not alarming, then, that Princeton’s WPRB has almost no campus audience. My friends are often surprised to hear, when I mention I work for WPRB, that Princeton does, in fact, have a student-run radio station. Even those who know WPRB exists tend to look at me skeptically, asking whether anyone “actually listens.”

It’s easy to see WPRB’s dwindling student listenership and write the station off as yet another casualty of the Digital Age. Yet, according to WPRB Educational Advisor Mike Lupica—who has worked at the station for nearly twenty years—Princeton students have never been WPRB’s target demographic. In fact, the station—whose FM signal stretches, on a clear day, from Newark, New Jersey, to Newark, Delaware—has always perceived itself as an independent entity existing outside, and even in spite of, the University’s authority.

This anti-establishment mentality is palpable in WPRB: A Haven For the Creative Impulse, an exhibition of documents, photographs, and memorabilia from WPRB’s history currently on display in Mudd Manuscript Library. Lupica, who curated the exhibit, said he got the idea after attending a similar exhibition at the University of Maryland’s WMUC. The station was celebrating an upcoming anniversary, and WMUC staff had collaborated with University archivists to produce what Lupica called a “top shelf” presentation of their history. On returning to Princeton, Lupica was inspired to tap the school’s wealth of archival resources in honor of WPRB’s own 75th anniversary.

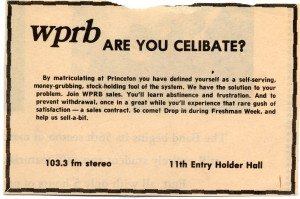

Despite its straight-laced academic venue, the display is anything but conventional. One 1986 recruitment ad for sales staff reminds freshmen, “By matriculating at Princeton, you have defined yourself as a self serving, money-grubbing, stock-holding tool of the system. We have the solution to your problems.”

This only partially tongue-in-cheek defiance characterizes the exhibit as a whole. Princeton’s logo is nowhere to be seen—instead, DIY-style cartoons depict cats in cars and green-haired teens eating cheese. On battered record sleeves, student reviewers debate the genius of experimental artists like Javek and Sun Ra. David Brooks might have called Princeton “the preppiest of the Ivy League schools,” but the station is, without a doubt, a thoroughly countercultural operation.

Unlike many campus radio stations, WPRB is an independent entity, almost entirely funded by community donations. While roughly two-thirds of its DJs are current Princeton students, the others are local underground music aficionados, some of whom drive from as far as Philadelphia to host a weekly radio show. In this way, WPRB is one of the few spaces on campus where Princeton ceases to be the isolated, self-contained entity it often seems to be.

In fact, it’s hard to believe the station is a part of campus at all. Though technically University property, the bunker-like basement offices in Bloomberg Hall, with their cluttered shelves and poster-plastered walls, are a far cry from the polished grandeur of Firestone library and Chancellor Green. For many of WPRB’s members—myself included—this is precisely what makes the station so attractive. “While svelte co-eds were friskily tossing lacrosse sticks and wearing diamond stud earrings, I lumbered around campus draped in a long coat and self loathing,” wrote Lily Prillinger ’97 in a testimonial for the exhibit. “I suppose it was inevitable that I would [join] the subterranean universe of WPRB.”

WPRB’s on-air content consistently favors creativity over conformity. As Summer Station Manger Zena Kesselman ’17 put it in her own testimonial, WPRB is an “alternate dimension where we are encouraged to produce anything but the ordinary.” Like many other WPRB DJs, Kesselman combines records, CDs, and digital streaming from a variety of online sources to produce a diverse, freeform show that incorporates everything from punk rock to poetry and challenges the lines between genres. This, in Lupica’s eyes, is radio as art. Freeform radio “turn[s] the act of being on the radio with a show into being an artist with a canvas,” he told me. “It’s a corny comparison, but it’s true.”

Like much avant-garde art, however, freeform radio isn’t designed for mass appeal. The station’s latest top charts include Sneaks, a Washington-based artist who combines spoken word with bass and drum beats, and a compilation album of underground electronic music from Peru. Last year, one of the most popular new releases came from Olivia Neutron John, an artist who plays, in Lupica’s words, “electronic free jazz with screaming over it.” Though diamonds in the rough to WPRB’s nonconformist listeners—who approach a radio show the way you might, say, an unsettling but innovative contemporary painting—these aren’t exactly crowd-pleasers. “It’s never going to cross over,” Lupica said of John’s work. “But on college radio, people are like, this is insane. I want to go see this. I want to go find out more about it.”

At Princeton, those listeners are few and far between. But with a 14-kw signal that reaches well beyond campus, the station doesn’t have to tailor its style to what Princeton students like. Having a stronger student following would also change the nature of the station itself. When, several months ago, I naively suggested to a fellow DJ that we should work on improving our campus presence, she objected that having more people involved in the station would ruin its covert, anti-establishment appeal. WPRB is, quite literally, underground—and that’s a point of pride.

I couldn’t help but feel a bit odd studying water-stained record sleeves and DJs’ irreverent doodles while standing in a well-lit, well-vacuumed room in Mudd. Passionately scrawled, occasionally profane reviews, fuzzy photographs of long-haired DJ’s—these artifacts from a world that prides itself on staying out of the public eye are now on display in transparent cases. It’s as if the station, in all its musty, unwashed, angst-ridden nonconformity has emerged from below ground and stepped onto Princeton’s campus for the first time—and the University is extending its arm. It’s weird. It’s awkward. From a curatorial standpoint, it’s quite impressive. It’s certainly not mainstream.

YAAAS KAT! YOU GO ! SLAY! PREACH IT! wprb is the fukn bomb

Woot Woot!